DINOSAURICON E

september 30, 2012 Plaats een reactie

E

- Echinodon Echinodon was een geslacht van plantenetende dinosauriërs behorend tot de Ornithischia, die tijdens het Late Jura leefde in het gebied van het huidige Engeland. De typesoort is Echinodon becklesii. syn : Saurechinodon Herbivore, Quadrupedal Ornithischia Suborder: Thyreophora? Family: Scelidosauridae? H 0.3 meters L 0.6 meters Late Jurassic

Discovered in England and described by Sir Richard Owen in 1861, Echinodon was once considered to be a fabrosaurid, a family name that has now been abandoned. It may have been related to Scutellosaurus, a plant-eater with small bony armor plates on its back. Evidence suggests that armor found in England in 1879 and thought to belong to a lizard, may belong to Echinodon, thus moving it into the mostly quadrupedal Thyreophora suborder of ornithischians.

Discovered in England and described by Sir Richard Owen in 1861, Echinodon was once considered to be a fabrosaurid, a family name that has now been abandoned. It may have been related to Scutellosaurus, a plant-eater with small bony armor plates on its back. Evidence suggests that armor found in England in 1879 and thought to belong to a lizard, may belong to Echinodon, thus moving it into the mostly quadrupedal Thyreophora suborder of ornithischians.

http://scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2007/05/24/galve-european-spinosaurines-c/ http://qilong.wordpress.com/2012/10/08/pegomastax-and-the-echinodonts/

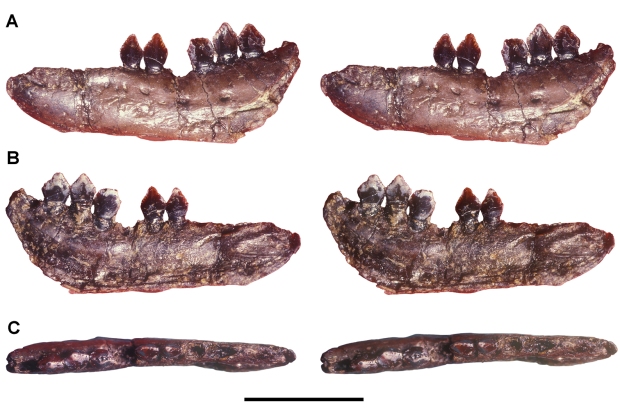

NHMUK 48215b, a paralectotype dentary referred to Echinodon becklesii (Owen, 1861). AfterSereno, 2012.

It was a theropod closely related to Torvosaurus, and may, in fact, be a junior synonym of that genus. Its fossils, including a partial skeleton, were found at Como Bluff, Wyoming.

http://dinosaurss.blog.cz/1105/edmarka

http://tolweb.org/NodosauridaeEdmontonia (meaning “From the Edmonton Formation”) was an armoured dinosaur, a part of the nodosaur family from the Late Cretaceous Period. It is named after the Edmonton Formation (now the Horseshoe Canyon Formation), the unit of rock it was found in. was bulky and tank-like at roughly 6.6 m (22 ft) long and 2m (6 ft) high.[citation needed] It had small, ridged bony plates on its back and head and many sharp spikes along its back and tail. The four largest spikes jutted out from the shoulders on each side, two of which were split into subspines in some specimens. Its skull had a pear-like shape when viewed from above.(information from Wikipedia.org

http://tolweb.org/NodosauridaeEdmontonia (meaning “From the Edmonton Formation”) was an armoured dinosaur, a part of the nodosaur family from the Late Cretaceous Period. It is named after the Edmonton Formation (now the Horseshoe Canyon Formation), the unit of rock it was found in. was bulky and tank-like at roughly 6.6 m (22 ft) long and 2m (6 ft) high.[citation needed] It had small, ridged bony plates on its back and head and many sharp spikes along its back and tail. The four largest spikes jutted out from the shoulders on each side, two of which were split into subspines in some specimens. Its skull had a pear-like shape when viewed from above.(information from Wikipedia.org

De lange schedels van een Edmontosaurus en een paard; beide hebben een lange schedel en grote maalkiezen

Hanenkam ontdekt

Wetenschappers hebben in Canada een bijzondere ontdekking gedaan. Ze troffen er de gemummificeerde resten van een eendensnaveldinosaurus met een hanenkam aan. Het bewijst voor het eerst dat deze dino’s een kleurige kam op de kop hadden die in veel opzichten overeenkomsten vertoont met de moderne hanenkam.

Het is niet ongewoon dat dinosaurussen worden teruggevonden met een bijzondere structuur op de kop. Denk maar eens aan de Triceratops met hoorns op de kop en dat enorme schild dat zijn kwetsbare nek beschermde. Maar dat zijn stuk voor stuk botstructuren. Een dinosaurus met een vlezige structuur op de kop is nog nooit ontdekt.

Gemummificeerd

Tot nu dan. In Canada troffen de onderzoekers de resten van een gemummificeerde eendensnaveldinosaurus aan. Het gaat om een Edmontosaurus regalis: een soort waar al diverse fossiele resten van zijn teruggevonden. En toch is deze vondst bijzonder. “We hebben reeds heel veel schedels van de Edmontosaurus gevonden, maar geen enkele vertoont aanwijzingen dat ze een grote, vlezige kam op de kop hadden,” vertelt onderzoeker Phil Bell. En dat is ook goed te verklaren. Omdat er geen bot in de kam zit, fossiliseert deze niet. Dat onderzoekers de hanenkam nu gedetecteerd hebben, is dan ook puur te danken aan het feit dat de Edmontosaurus die de onderzoekers ontdekten, gemummificeerd was.

De vondst trekt het uiterlijk van diverse dino’s waarmee we juist zo vertrouwd zijn geraakt, in twijfel en is volgens Bell, erg belangrijk. Normaal gesproken fossiliseert een vleesachtige structuur zoals een hanenkam namelijk niet.

“Het is alsof we voor het eerst hebben ontdekt dat olifanten slurven hebben. We hebben veel schedels van Edmontosaurussen gevonden, maar nooit eerder waren er aanwijzingen dat ze een vlezige kam op hun hoofd hadden.”

Bell vermoedt dat ook andere dinosauriërs hanenkammen hadden. “Er is geen reden om aan te nemen dat andere vreemde vlezige structuren niet aanwezig waren op heel veel andere dinosaurussen, waaronder(bijvoorbeld ) de T. rex of de Triceratops,” stelt Bell.

Het is nog onduidelijk waar de hanenkam van de dinosaurussen voor diende. Vergelijkbare structuren komen ook voor bij moderne dieren zoals kameleons en hanen en hagedissen en dienen meestal om indruk te maken op mogelijke seksuele partners en ze zodoende te versieren . Mogelijk gold dat ook voor de dinosaurus.

De afbeelding bovenaan dit artikel is gemaakt door Julius Csotonyi © Bell, Fanti, Currie, Arbour, Current Biology.

Edmontosaurus has been described in detail from several specimens. Like other hadrosaurids, it was a bulky animal with a long, laterally flattened tail and a head with an expanded, duck-like beak. The skull had no hollow or solid crest, unlike many other hadrosaurids. The fore legs were not as heavily built as the hind legs, but were long enough to be used in standing or movement. Edmontosaurus was among the largest hadrosaurids: depending on the species, a fully grown adult could have been 9 meters (30 ft) long, and some of the larger specimens reached the range of 12 meters (39 ft) to 13 meters (43 ft) long. Its weight was on the order of 4.0 metric tons (4.4 short tons). At the present, E. regalis is the largest species, although its status may be challenged if the large hadrosaurid Anatotitan copei is shown to be the same as Edmontosaurus annectens, as put forward by Jack Horner and colleagues in 2004 (this remains to be tested by other authors). The type specimen of E. regalis, NMC 2288, is estimated as 9 to 12 meters (30 to 39 ft) long. E. annectens was somewhat shorter. Two well-known mounted skeletons, USNM 2414 and YPM 2182, measure 8.00 meters (26.25 ft) long and 8.92 meters (29.3 ft) long, respectively. However, there is at least one report of a much larger potential E. annectens specimen, almost 12 meters (39 ft) long. E. saskatchewanensis was smaller yet, with its full length estimated as 7 to 7.3 meters (23 to 24.0 ft).

The skull of a fully grown Edmontosaurus was around a meter (or yard) long, with E. regalis falling on the longer end of the spectrum and E. annectens falling on the shorter end. The skull was roughly triangular in profile, with no bony cranial crest. Viewed from above, the front and rear of the skull were expanded, with the broad front forming a duck-bill or spoon-bill shape. The beak was toothless, and both the upper and lower beaks were extended by keratinous material. Substantial remains of the keratinous upper beak are known from the “mummy” kept at the Senckenberg Museum. In this specimen, the preserved nonbony part of the beak extended for at least 8 centimeters (3.1 in) beyond the bone, projecting down vertically. The nasal openings of Edmontosaurus were elongate and housed in deep depressions surrounded by distinct bony rims above, behind, and below. In at least one case (the Senckenberg specimen), rarely preserved sclerotic rings were preserved in the eye sockets. Another rarely seen bone, the stapes (the reptilian ear bone), has also been seen in a specimen of Edmontosaurus.

The number of vertebrae differs between specimens. E. regalis had thirteen neck vertebrae, eighteen back vertebrae, nine hip vertebrae, and an unknown number of tail vertebrae. A specimen once identified as belonging to Anatosaurus edmontoni (now considered to be the same as E. annectens) is reported as having an additional back vertebra and 85 tail vertebrae, with an undisclosed amount of restoration. Other hadrosaurids are only reported as having 50 to 70 tail vertebrae, so this appears to have been an overestimate. The anterior back was curved toward the ground, with the neck flexed upward and the rest of the back and tail held horizontally. Most of the back and tail were lined by ossified tendons arranged in a latticework along the neural spines of the vertebrae. This condition has been described as making the back and at least part of the tail “ramrod” straight.

Multiple specimens of Edmontosaurus have been found with preserved skin impressions. Several have been well-publicized, such as the “Trachodon mummy” of the early 20th century, and the specimen nicknamed “Dakota”, the latter apparently including remnant organic compounds from the skin. Because of these finds, the scalation of Edmontosaurus is known for most areas of the body.

Skin impression from the abdomen of Edmontosaurus annectens

Skin impression from the abdomen of Edmontosaurus annectens

Luis Chiappe | Lorraine Meeker AMNH

Edmontosaurus was a hadrosaurid (a duck-billed dinosaur), a member of a family of dinosaurs which to date are known only from the Late Cretaceous. It is classified within the Hadrosaurinae, a clade of hadrosaurids which lacked hollow crests. Other members of the group include Brachylophosaurus, Gryposaurus, Lophorhothon, Maiasaura, Naashoibitosaurus, Prosaurolophus, and Saurolophus. It was either closely related to or the same as Anatotitan, another large hadrosaurid from various latest Cretaceous formations of western North America. The giant Chinese hadrosaurine Shantungosaurus is also anatomically similar to Edmontosaurus; M. K. Brett-Surman found the two to differ only in details related to the greater size of Shantungosaurus, based on what had been described of the latter genus.While the status of Edmontosaurus as a hadrosaurine has not been challenged, its exact placement within the clade is uncertain. Early phylogenies, such as that presented in R. S. Lull and Nelda Wright’s influential 1942 monograph, had Edmontosaurus and various species of Anatosaurus (most of which would be later reevaluated as additional species or specimens of Edmontosaurus) as one lineage among several lineages of “flat-headed” hadrosaurs. One of the first analyses using cladistic methods found it to be linked with Anatotitan and Shantungosaurus in an informal “edmontosaur” clade, which was paired with the spike-crested “saurolophs” and more distantly related to the “brachylophosaurs” and arch-snouted “gryposaurs”. A 2007 study by Terry Gates and Scott Sampson found broadly similar results, in that Edmontosaurus remained close to Saurolophus and Prosaurolophus and distant from Gryposaurus, Brachylophosaurus, and Maiasaura.

Edmontosaurus has had a long and complicated history in paleontology, having spent decades with various species classified in other genera. Its taxonomic history intertwines at various points with the genera Agathaumas, Anatosaurus, Anatotitan, Claosaurus, Hadrosaurus, Thespesius, and Trachodon, and references predating the 1980s typically use Anatosaurus, Claosaurus, Thespesius, or Trachodon for edmontosaur fossils (excluding those assigned to E. regalis), depending on author and date. Although Edmontosaurus was only named in 1917, its oldest well-supported species (E. annectens) was named in 1892 as a species of Claosaurus, and scrappier fossils that may belong to it were described as long ago as 1871.The first described remains that may belong to Edmontosaurus were named Trachodon atavus in 1871 by Edward Drinker Cope. This species was assessed without comment as a synonym of Edmontosaurus regalis in two reviews, although atavus predates regalis by several decades. In 1874 Cope named but did not describe Agathaumas milo for a sacral vertebra and shin fragments from the late Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Laramie Formation of Colorado. Later that same year, he described these bones under the name Hadrosaurus occidentalis. The bones are now lost. As with Trachodon atavus, Agathaumas milo has been assigned without comment to Edmontosaurus regalis in two reviews, although predating regalis by several decades. Neither species has attracted much attention; both are absent from Lull and Wright’s 1942 monograph, for example. A third obscure early species, Trachodon selwyni, described by Lawrence Lambe in 1902 for a lower jaw from what is now known as the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, was erroneously described by Glut (1997) as having been assigned to Edmontosaurus regalis by Lull and Wright. It was not, instead being designated “of very doubtful validity.”

A 1905 chart showing the relatively small brains of a Triceratops (top) and EdmontosaurusThe brain of Edmontosaurus has been described in several papers and abstracts through the use of endocasts of the cavity where the brain had been. E. annectens and E. regalis, as well as specimens not identified to species, have been studied in this way. The brain was not particularly large for an animal the size of Edmontosaurus. The space holding it was only about a quarter of the length of the skull, and various endocasts have been measured as displacing 374 milliliters (13 US fl oz)[76] to 450 milliliters (15 US fl oz), which does not take into account that the brain may have occupied as little as 50% of the space of the endocast, the rest of the space being taken up by the dura mater surrounding the brain. For example, the brain of the specimen with the 374 millilitre endocast is estimated to have had a volume of 268 milliliters (9 US fl oz). The brain was an elongate structure, and as with other non-mammals, there would have been no neocortex. Like Stegosaurus, the neural canal was expanded in the hips, but not to the same degree: the endosacral space of Stegosaurus had 20 times the volume of its endocranial cast, whereas the endosacral space of Edmontosaurus was only 2.59 times larger in volume.

As a hadrosaurid, Edmontosaurus was a large terrestrial herbivore. Its teeth were continually replaced and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its broad beak to cut loose food, perhaps by cropping, or by closing the jaws in a clamshell-like manner over twigs and branches and then stripping off the more nutritious leaves and shoots. Because the tooth rows are deeply indented from the outside of the jaws, and because of other anatomical details, it is inferred that Edmontosaurus and most other ornithischians had cheek-like structures, muscular or non-muscular. The function of the cheeks was to retain food in the mouth. The animal’s feeding range would have been from ground level to around 4 meters (13 ft) above.Before the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing interpretation of hadrosaurids like Edmontosaurus was that they were aquatic and fed on aquatic plants. An example of this is William Morris’s 1970 interpretation of an edmontosaur skull with nonbony beak remnants. He proposed that the animal had a diet much like that of some modern ducks, filtering plants and aquatic invertebrates like mollusks and crustaceans from the water and discharging water via V-shaped furrows along the inner face of the upper beak. This interpretation of the beak has been rejected, as the furrows and ridges are more like those of herbivorous turtle beaks than the flexible structures seen in filter-feeding birds.The prevailing model of how hadrosaurids fed was put forward in 1984 by David B. Weishampel. He proposed that the structure of the skull permitted motion between bones that led to backward and forward motion of the lower jaw, and outward bowing of the tooth-bearing bones of the upper jaw when the mouth was closed. The teeth of the upper jaw would grind against the teeth of the lower jaw like rasps, processing plant material trapped between them. Such a motion would parallel the effects of mastication in mammals, although accomplishing the effects in a completely different way. An important piece of evidence for Weishampel’s model is the orientation of scratches on the teeth, showing the direction of jaw action. Other movements could produce similar scratches, though, such as movement of the bones of the two halves of the lower jaw. Not all models have been scrutinized under present techniques.Weishampel developed his model with the aid of a computer simulation. Natalia Rybczynski and colleagues have updated this work with a much more sophisticated three-dimensional animation model, scanning a skull of E. regalis with lasers. They were able to replicate the proposed motion with their model, although they found that additional secondary movements between other bones were required, with maximum separations of 1.3 to 1.4 centimeters (0.51 to 0.55 in) between some bones during the chewing cycle. Rybczynski and colleagues were not convinced that the Weishampel model is viable, but noted that they have several improvements to implement to their animation. Planned improvements include incorporating soft tissue and tooth wear marks and scratches, which should better constrain movements. They note that there are several other hypotheses to test as well. Further work by Casey Holliday and Lawrence Witmer found that ornithopods like Edmontosaurus lacked the types of skull joints seen in those modern animals that are known to have kinetic skulls (skulls that permit motion between their constituent bones), such as squamates and birds. They proposed that joints that had been interpreted as permitting movement in dinosaur skulls were actually cartilaginous growth zones

Both of the “mummy” specimens collected by the Sternbergs were reported to have had possible gut contents. Charles H. Sternberg reported the presence of carbonized gut contents in the American Museum of Natural History specimen, but this material has not been described. The plant remains in the Senckenberg Museum specimen have been described, but have proven difficult to interpret. The plants found in the carcass included needles of the conifer Cunninghamites elegans, twigs from conifer and broadleaf trees, and numerous small seeds or fruits. Upon their description in 1922, they were the subject of a debate in the German-language journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift. Kräusel, who described the material, interpreted it as the gut contents of the animal, while Abel could not rule out that the plants had been washed into the carcass after death.At the time, hadrosaurids were thought to have been aquatic animals, and Kräusel made a point of stating that the specimen did not rule out hadrosaurids eating water plants. The discovery of possible gut contents made little impact in English-speaking circles, except for another brief mention of the aquatic-terrestrial dichotomy, until it was brought up by John Ostrom in the course of an article reassessing the old interpretation of hadrosaurids as water-bound. Instead of trying to adapt the discovery to the aquatic model, he used it as a line of evidence that hadrosaurids were terrestrial herbivores. While his interpretation of hadrosaurids as terrestrial animals has been generally accepted, the Senckenberg plant fossils remain equivocal. Kenneth Carpenter has suggested that they may actually represent the gut contents of a starving animal, instead of a typical diet. Other authors have noted that because the plant fossils were removed from their original context in the specimen and were heavily prepared, it is no longer possible to follow up on the original work, leaving open the possibility that the plants were washed-in debris.

°

Edmontosaurus

Edmontosaurus was a Herbivore from the Late Cretaceous Period.

Edmontosaurus

Edmontosaurus meaning ‘Edmonton lizard’ (after where it was found, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and Greek sauros meaning lizard) was a hadrosaurid dinosaur genus from the Maastrichtian, the last stage of the Cretaceous Period, 71-65 million years ago. A fully-grown adult could have been up to 9 metres (30 feet) long and some of the larger species reached 13 metres (43 feet). Its weight was in the region of 3.5 tonnes, making it one of the largest hadrosaurids.

Edmontosaurus was een hadrosauriër of eendesnaveldinosauriër behorend tot de groep van de Edmontosaurini. Het was een herbivoor zonder klauwen. Wel kon hij wellicht door een op te zwellen neuszak zijn soortgenoten waarschuwen voor gevaar. Hij was familie vanAnatotitan en leefde tijdens het late Krijt in het huidige Noord-Amerika.

De eerste soort, E. regalis werd in 1917 beschreven door Lawrence Morris Lambe. De geslachtsnaam verwijst naar de stad Edmonton in Canada; de soortaanduiding betekent: “koninklijk” en verwijst naar de enorme omvang van het dier dat een lengte kon bereiken van zo’n dertien meter. Er wordt een tweede soort onderscheiden: E. annectens, in 1892 door Othniel Charles Marsh beschreven als Claosaurus annectus. De derde soort is E. saskatchewanensis. Beide laatste zijn een tijdje ondergebracht bij Anatosaurus.

Een skelet van Edmontosaurus is te zien in Naturalis

Sommige dinosaurussen zijn zo groot dat ze niet op één verdieping van een gebouw zouden passen, zoals deze Camarasaurus in het museum Naturalis in Leiden

Rechts staat het skelet van edmontosaurus opgesteld

°

- Efraasia Efraasia is een uitgestorven monotypisch geslacht van plantenetende basale sauropodomorfe dinosauriërs. De enige soort, Efraasia minor, leefde ongeveer 210 miljoen jaar geleden, tijdens het Opper-Trias, in het gebied van het huidige Duitsland.

Efraasia

http://www.dinosoria.com/prosauropodes.htm

Skull reconstruction of Efraasia minor (based on SMNS 12216, 12684, 12667). From Yates, 2003. Scale bar is 5 cm.

http://www.palaeocritti.com/by-group/dinosauria/sauropoda/efraasia

°

- Einiosaurus—> Einiosaurus is een uitgestorven geslacht van plantenetende ornithischische dinosauriërs, behorend tot de groep van de Ceratopia, dat tijdens het Laat-Krijt leefde in het gebied van het huidige Noord-Amerika

Einiosaurus had a large downward-curving nasal horn.

Einiosaurus had a large downward-curving nasal horn.

MfN Berlin Elaphrosaurus mount

http://dinosaurpalaeo.wordpress.com/2012/10/04/theropod-thursday-29-elaphrosaurus/

- Elmisaurus

- Elopteryx

- Elosaurus – junior synonym of Apatosaurus

- Elrhazosaurus

- “Elvisaurus” – nomen nudum; Cryolophosaurus

- Emausaurus

- Embasaurus

- Empaterias – misspelling of Epanterias

- Enigmosaurus

- Eobrontosaurus

- Eocarcharia

- Eoceratops – junior synonym of Chasmosaurus

- Eocursor

- Eodromaeus

- “Eohadrosaurus” – nomen nudum; Eolambia

- Eolambia

- Eolosaurus[4] – junior synonym of Aeolosaurus

- Eomamenchisaurus

theropods <—documentatiemap & beeldmateriaal

°

Suborder: Theropoda

Superfamily: Tyrannosauroidea

Genus: Eotyrannus

- Epachthosaurus

- Epanterias – may be Allosaurus

- “Ephoenosaurus” – nomen nudum; Machimosaurus (a crocodilian)

- Epicampodon – actually a proterosuchid archosauriform

- Epichirostenotes

(Greek for “lizard in the tree”); Woodlands of Asia

Late Jurassic (150 million years ago)

About 6 inches long and one pound Probably omnivorous

Tiny size; long arms with clawed handsArchaeopteryx gets all the press, but there’s a convincing case to be made that Epidendrosaurus was the first reptile to be closer to a bird than to a dinosaur. This pint-sized theropod was less than half the size of its more famous cousin, and it’s a sure bet that it was covered with feathers. Most notably, Epidendrosaurus appears to have been adapted to an arboreal (tree-dwelling) lifestyle–its small size would have made it a simple matter to hop from branch to branch, and its long, curved claws were likely used to pry insects from tree bark.

So was Epidendrosaurus really a bird rather than a dinosaur?

As with all of the feathered “dino-birds,” as these reptiles are called, it’s impossible to say.

It’s better to think of the categories of “bird” and “dinosaur” as lying along a continuum, with some genera closer to either extreme and some smack in the middle.

- Erectopus —>Erectopus is een geslacht van vleesetende theropode dinosauriërs, behorend tot de Tetanurae, dat tijdens het vroege Krijt leefde in het gebied van het huidige Frankrijk. De enige benoemde soort is Erectopus superbus.

- Erlicosaurus – misspelling of Erlikosaurus

- Erlikosaurus

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/12/121219174154.htm

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0052289

- Eshanosaurus

- “Euacanthus” – nomen nudum; junior synonym of Polacanthus

- (Ichnofossil )Eubrontes (?) Glenrosensies ,

track with partly mud-collapsed digits

Track name: Eubrontes glenrosensis sp.

Somervell County, Texas

Glen Rose Limestone

Lower Cretaceous (110 million years)

Eubrontes (?) glenrosensis SHULER, published by Adams et al. in Palaeontologia Electronica in 2010.

(The “toes” in the figure above) =

_The figure above is both an indirect vindication of Weems’ work, and a warning: many dinosauriformian and dinosaurian lineages are so convergent that they make highly similar tracks across vast distances in space and time!

Weems in 2003, in a very detailed study of the pedal morphology and posture of Plateosaurus, noted the excellent correlation between Plateosaurus and the Connecticut Eubrontes tracks

Weems, R.E. 2003. Plateosaurus foot structure suggests a single trackmaker for Eubrontes and Gigandipus footprints, p. 293–313.

Eubrontes

E. Hitchcock 1845, p. 23.

Type species: Eubrontes giganteus E. Hitchcock 1845, p. 23.

Lithographs and photographs of Eubrontes giganteus and referred specimens (from Olsen et al., 1998):(Scale, 5 cm, in the lithographs added by authors)

A, lithograph of AC 15/3, Hitchcock (1836, Fig. 21)B, lithograph of AC 15/3, Buckland (1836, Pl. 26b, Fig. 1)

C, lithograph of AC 15/3, Hitchcock (1848, Pl. 1, Fig. 1)

D, lithograph of AC 15/3, Hitchcock (1858, Pl. 57, fig 1)

- Eucamerotus

- Eucentrosaurus – junior synonym (unneeded replacement name) of Centrosaurus

- Eucercosaurus – possibly Anoplosaurus

- Eucnemesaurus

- Eucoelophysis – actually a non-dinosaurian dinosauromorph

- “Eugongbusaurus” – nomen nudum

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Euoplocephalus-tutus-1.jpg //Euoplocephalus-Skeleton in im Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt//

Life restoration of Euoplocephalus.

Life restoration of Euoplocephalus.

- Euoplocephalus Euoplocephalus Thyreophora/Ankylosauridae

Built like an armored tank, Euoplocephalus ambled through the late Cretaceous landscape, well equipped to withstand attack from any other dinosaur. Low slung and broad, the back of Euoplocephalus bore rows of bony shields with some taller spikes over the shoulders and at the base of the tail. There were also spikes on the dinosaur’s cheeks and behind each eye, protecting the head.

The most lethal weapon in Euoplocephalus’s armory was the double-headed club at the end of the long, stiffened tail. The base of the tail was quite flexible, but the last third was welded into a stiff rod by long struts growing out of each vertebra. The tail club could be swung most effectively from side to side, swiping at the feet of an attacking predator. If it connected with full force, it could shatter the ankle bones of the attacker, a wound that could later prove fatal.

Euoplocephalus had a compact, rounded head. Like other ankylosaurids, but unlike nodosaurids, it had a complex and convoluted nasal passage in the skull, but the function that this served is not clear. Perhaps the extra length given by the twists and loops allowed air to be warmed while the animal was breathing in, or perhaps this passage collected moisture from air being exhaled. The passage may also have been lined with sensors that gave Euoplocephalus an enhanced sense of smell for detecting food, predators, or potential mates.

The mouth had a broad beak at the front and a wide palate lined with small teeth. This arrangement suggests that Euoplocephalus was not particularly selective about what it ate and would consume almost any plant material that it could reach.

Around 40 specimens of Euoplocephalus have been found. All were isolated finds, which suggests thst these animals were loners rather than pack or herd animals. Packs and herds provided plant-eaters with a defense against predators but, perhaps because it was so heavily armored, Euoplocephalus had no need to rely on group behavior for protection.

- Eupodosaurus – a nothosaur synonymous with Lariosaurus

- “Eureodon” – nomen nudum; Tenontosaurus

- Eurolimnornis – possibly a bird

- Euronychodon

- Europasaurus

- Euskelosaurus

- Eustreptospondylus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_dinosaurs

( March 6, 2009

March 6, 2009

” a trackmaker assignment is a hypothesis.

Eubrontes isn’t a dinosaur body-fossil genus. It’s an ichnotaxon–in this case a footprint genus. There are no Eubrontes skeletons out there. The name is restricted to the footprint morphotype alone. Ignoring the issues with slapping Latin bionomials on sedimentary structures, this is a common practice and Eubrontes fossils represent a fairly characteristic type of footprint shape found across North America in Lower Jurassic rocks.

The question of what animal made Eubrontes is a different issue, but identifying a footprint as a Eubrontes track is a matter of studying the footprint itself and comparing it to other footprints. There need not be dinosaur skeletal feet preserved nearby that fit the tracks. Again, the issue of who made the fooprint is a different issue from figuring out whether or not the track morphology is consistent with the morphotype that is known as Eubrontes. ”

http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2009/03/06/how-did-dinosaurs-sit-down/